The service paints many vivid pictures of what happens on the Christian way.

If you are engaged to be married and looking for a church to be married in, then congratulations! A wedding is one of life's great moments, a time of solemn commitment as well as good wishes, feasting and joy.

If someone you know and love has died, a funeral led by a Church of England minister can be held in church, in a churchyard, by a graveside, or at a crematorium. The minister will be there to support you every step of the way.

St Mary, Skipenbeck

The name ‘Skirpenbeck’ comes from the old Norse words ‘skerping’ and ‘bekkr’ which translate as ‘barren land beside a stream’. ‘Scarpenbec’, as it is referred to in the Domesday Book, was held by Forne son of Sigulf and later came under the lordship of Odo the Bowman. The manor of Skirpenbeck was later purchased by William de Chauncy who had fought with William the Conqueror.

The church at Skirpenbeck, dedicated to St. Mary, dates from the twelfth century. In the middle of that century it was given to the Abbey at Whitby by Walter de Chancy and his son. Whitby Abbey held the church and its patronage until, at the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the sixteenth century, it passed to the Crown. In the Middle Ages there was also a chantry chapel at Skirpenbeck. This is sometimes described as being dedicated to St. Agatha. However, a source connected to St. Agatha’s Abbey at Easby, near Richmond, refers to St. Sylvester’s Chapel at Skirpenbeck where prayers were said for John Romayn, an Italian churchman who was the first sub-dean of York Minster before becoming Archdeacon of Richmond. He died around 1255. St. Sylvester was pope from 314 AD until his death in 335 AD.

The present church at Skirpenbeck has an eighteenth-century brick tower. The nave and chancel, however, are Norman. In the east wall of the nave is an original slit window. There are other examples of these splayed or slit windows elsewhere in the nave. There is a blocked doorway in the north wall of the nave. In the south wall of the chancel is a doorway with a square hoodmould – the name given to a projecting lip of masonry above a door or window - in the form of a lintel.

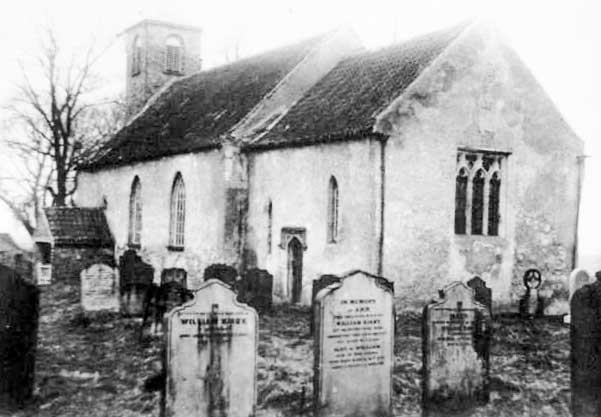

St. Mary’s Church, Skirpenbeck, showing the eighteenth-century brick tower and the twelth-century nave walls with slit windows.

The twelfth-century tub font with, centre, details of the carving. On the left is a detail from the South Door.

The twelfth-century font, like that in nearby Bugthorpe, is deep enough to allow for total immersion of a child at baptism. It is decorated with intersecting arcades.

Other early features to note are the Romanesque details on the South Doorway, now fronted by a nineteenth-century porch. The capital on the left-hand side shows clearly upright lines or stems leading to curved patterns known as volutes. Beneath the volutes are panels bearing a saltire cross. The right-hand capital has lost its carvings but some trellis-work is visible next to it. The simple, unadorned yet striking chancel arch also dates from the twelfth-century.

The nave at Skirpenbeck seen from the Norman chancel arch. At the far end in the centre is the eighteenth-century tower and belfry.

The Romanesque Chancel Arch viewed from the nave of Skirpenbeck Church,

The church was extensively restored in 1893-94. On 15th April, 1893, the Yorkshire Gazette reported a parishioners’ meeting at Skirpenbeck which was convened in the school room ‘to consider the propriety of restoring the old Parish Church’. The Rev. T. H. Berry, Rector of Skirpenbeck presided, assisted by the Rev. H. L. Puxley, Rector of Catton and Rural Dean. The report published a list of people who had already promised subscriptions: Mr Henry Darley, £100; the Rector and his family, £100; Mr J. H. Ware, £20; the Rev. C. Johnstone, £20; the Rev. C. O. Trotter, £5; the Rev. H. L. Puxley, £5; and others.’ Proposed by Mr G. Beal and seconded by Mr M. Oxtoby and carried unanimously: ‘that the time had fully come for steps to be taken to restore the Parish Church’.

On 30th September, 1893, the York Herald reported that the Consistory Court at York had granted a faculty ‘to the vicar and churchwardens at Skirpenbeck to re-floor, re-seat, re-roof and re-fit up the church and make certain other alterations’. The church was re-opened at a service led by the Archbishop of York.

The inscriptions on the gravestones in the foreground are very clear indeed. The gravestones in the churchyard show the long association of families such as Kirby, Beal, Oxtoby and Ware – to name but a few – with the parish.

Skirpenbeck Church from the east prior to restoration in 1893-94.

That seating in church could sometimes be a contentious issue is shown by a court case reported in the York Herald of 6th August, 1870. This involved a claim for two years’ Easter dues which was brought by Peter Iveson against Thomas Holden. ‘Plaintiff had been parish clerk and sexton for thirty years, and had for eighteen or twenty years received 1s. 7d. a year of the defendant, which had always been collected at Easter.’ William Ware, land agent and surveyor, told the court that he had been churchwarden for ten or eleven years. He ‘produced terriers of the parish since 1809 showing the amounts payable to the clerk and sexton by farmers and others’. In reply, Thomas Holden said that ‘he never refused payment until he had reason to complain of his seat at church not being properly cleaned’. Peter Iveson said that the seat had been cleaned along with the others until Thomas Holden withheld payment, after which ‘he admitted that for some time he had neglected to clean it’. Judgment was in favour of Peter Iveson.

In another case brought by Peter Iveson for what he saw as his entitlement to Easter Dues, he was unsuccessful. In the same newspaper report we read that George Brown, a tailor of Skirpenbeck, told the court that ‘the cottage he occupied was included in a farm of Mr.Morley, and that he was merely an undertenant, and not liable for payment of the dues’. Indeed, ‘put of the nineteen years he had been in the parish he had only paid seven years’. The plaintiff, Peter Iveson, was non-suited. The Visitation Returns for the Diocese of York offer a fascinating insight into Skirpenbeck Church at two precise moments in its history. In 1743, the time of Archbishop Herring’s Visitation, Skirpenbeck did not have a resident incumbent. In fact, it did not even have a curate living in the parish. The rector, John Dealtry, lived at Bishopthorpe. His curate, William Sclater, looked after Bishop Wilton as well as Skirpenbeck and lived in ‘Goulthorpe’ which was midway between the two parishes.

The Rev. Dealtry provided the following information about William Sclater: ‘He has been my curate near 6 years and is duly qualified according to the Canons in that behalf, for taking care of both the parishes. I allow him £30 per annum and the surplice-fees. My curate performs divine service alternately morning and afternoon in this church and Bishop Wilton with a sermon every Sunday and on Christmas Day, Innocents’ Day, Good Friday, Easter Tuesday, Ash Wednesday, Ascension Day and all the holidays appointed by the government.’ The sacrament was administered at Skirpenbeck five times a year, twice at Easter.

Another person who played a role in offering a Christian education to at least some children in Skirpenbeck was John Playforth. Rev. Dealtry explains that there is no public or charity school in the village, adding:

About 16 boys and girls are taught by John Playforth to read and write the English language. He is supported by a voluntary contribution of one guinea yearly from me and 2s. 6d. per quarter paid by the parents or guardians for each child, according to whose will they are afterwards employed. He teaches in his own house and takes care to instruct them in the principles of the Christian religion according to the Church of England and to bring them duly to church as the Canon requires.

It is interesting that girls as well as boys were pupils under the tutelage of John Playforth.

In 1840, Mitford Bullock became the incumbent at Skirpenbeck. Archbishop Thompson’s Visitation Returns for the Diocese of York, 1865, report that at Skirpenbeck there was ‘Divine Service on Sundays, Morning and Evening, when a Sermon of Lecture is given, the former commencing at 10 o’clock, the latter at half past two o’clock’. Children received instruction from Church Catechism and Scripture,

‘generally in an afternoon service’. The average congregation size was fifty out of a parish population of almost two hundred. ‘In Summer the congregation increases. In winter it decreases owing to the weather.’ As for the Sunday School supported by the Rev. Bullock and one of his parishioners, that averaged ‘from sixty to twenty each Sunday’. There had been no recent alterations to the fabric of the church.

Another Skirpenbeck incumbent to be mentioned in the newspapers was the Rev. J. K. Walker. Under the heading ‘Midnight Pilgramage to East Riding Village’, a reporter writing in the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer on 23rd May, 1930, described a midnight visit to Skirpenbeck to listen to a nightingale singing in a tree at Rectory Farm. While he was there, twenty or thirty more people arrived in the village. ‘Mr Hotham, the occupier of the farm, told [him] that this sort of thing went on every night, and at the week-ends the number of interested visitors was enormous.’ Such was the disturbance in Skirpenbeck that one sleep-deprived villager threatened to shoot the nightingale, a proposal which horrified not only the farmer at Rectory Farm but also Rev. Walker

Rectory Farm, as explained in a report from the Yorkshire Evening Post of 24th May, 1930, was the property of the Church. The Rector, for one, welcomed ‘this newcomer to his choir’, saying:

I can lie in bed and listen to the nightingale. We do not mind other people listening as long as they do not make a noise. I can now distinguish the bird’s song easily in the daytime, and, as a matter of fact, the nightingale sings quite a lot during the day.

Rev. Walker was Rector of Skirpenbeck with Full Sutton. He left in 1940 to take the living of Luttons Ambo with Cowlam.

Given the proximity of Skirpenbeck to Stamford Bridge, scene of the famous battle of 1066 which saw King Harold defeat the forces of Harold Hardrada of Norway, it is not surprising that land around the present church is believed to be the burial ground of some of those who fell in the battle.

On 25th February, 1930, the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer reported: ‘A grave-digger in the village of Skirpenbeck, near Stamford Bridge, has discovered, four feet below the ground surface, the skeletons of six men lying close together.’ The remains were believed to be those of men buried after the Battle of Stamford Bridge. The report continues: ‘The skeletons are all of large-framed men. Their jaw bones were fully one and a half inches in width, and in two of the cases the bottom sets of teeth were complete and in a good state of preservation.’ Odd skeletons had been discovered prior to this date but never so many buried together.

The memorial to Richard Paget and his family.

Beneath the monument is a curiously enigmatic and cryptic inscription.

Returning to the interior of Skirpenbeck Church, there are a number of items of interest. On the south-west wall of the nave is a wall or epitaph monument in memory of Richard Paget and his family.

Here sleepeth the bodie of Mr. Rich: Paget with his two children expecting the last trumpe, whose soule was translated to blisse, June 17, 1636: when he was aged 51 yea: He was the sonne of Mr. Willaim Paget Batchelour in divinity fellow in Queens Colledg in Cambridg & one of the 4 licensed preachers in the beginning of Queen Eliza: reigne and sometimes the faithfull Pastor of this place.

According to his will, Richard Paget was ‘of York’ but this monument, by reference to his father, establishes his connection to Skirpenbeck. The list of incumbents at Skirpenbeck shows not only ‘William Parchett’ in 1571 but also his successor, a ‘John Pachet’ in 1599.

Originally the moment was to be found on the north wall of the chancel, a much more prestigious location near the altar at the east end of the church. A faculty of 1895 authorised its removal to its present location when a vestry was built on the north side of the chancel. Owing to damp which caused surface erosion and caused the skull to become detached from the rest of the monument, not to mention rendering much of the inscription illegible, the monument was removed from the church in 1988 and restored by Messrs. Guidici-Martin of Northamptonshire.

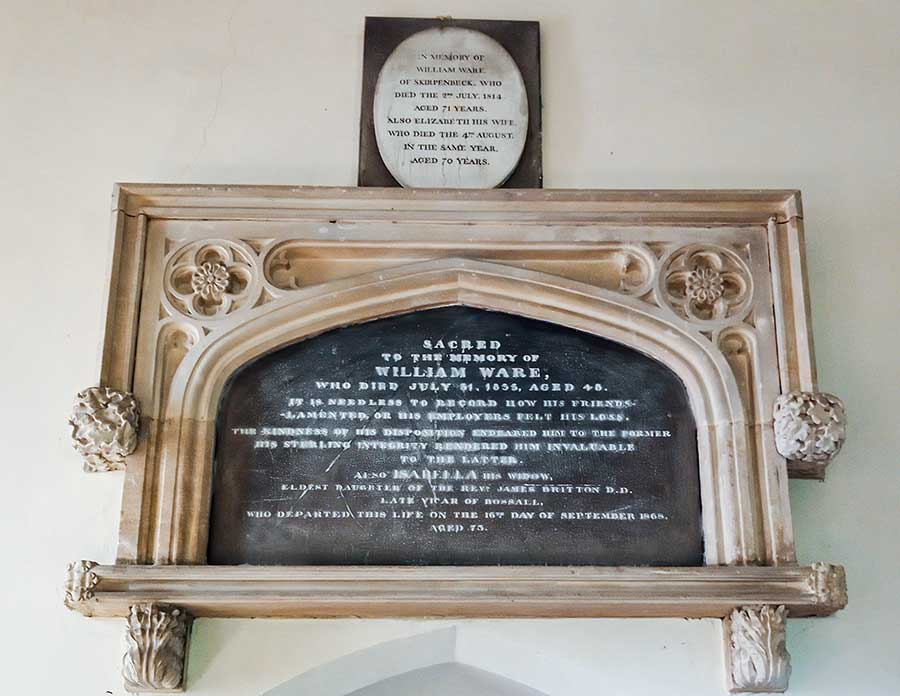

There is a memorial on the north wall of the nave to William Ware. The Ware family have been connected with Skirpenbeck for generations. There are many gravestones in the churchyard bearing their name.

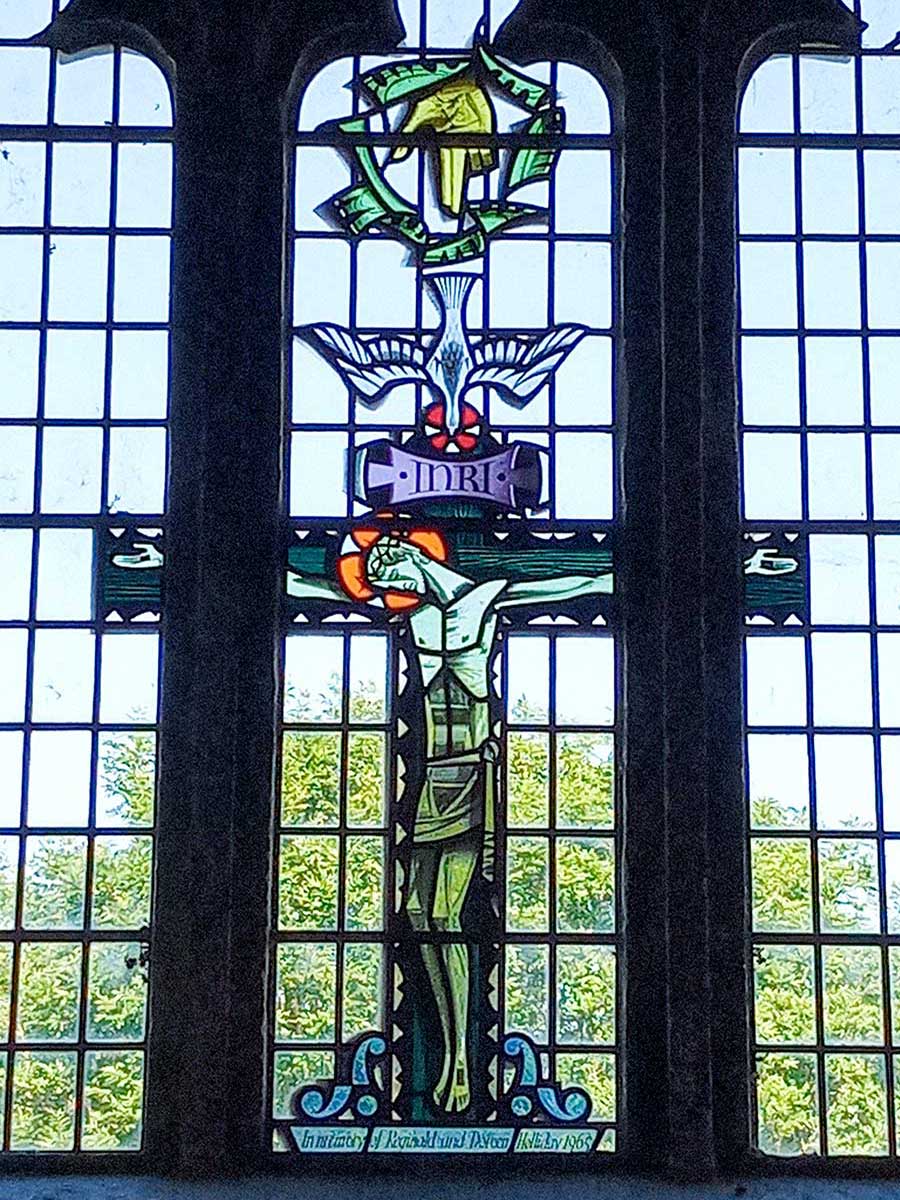

The East Window in Skirpenbeck Church.

The clear glass allows the natural world – the sky and trees – to come inside the church.

The eighteenth-century tower at Skirpenbeck with later afternoon sunlight casting its shadow.

The windows in the tower match the design of the medieval windows in the nave.

Skirpenbeck has been home to several people who became eminent in the wider world in their chosen sphere or vocation.

Born at Allerthorpe in 1807, Thomas Cooke attended Pocklington School before he was apprenticed to his father who was a shoemaker. He was unhappy in this and taught himself geometry and mathematics. When he was just seventeen years old, Thomas Cooke became a teacher at a school in Skirpenbeck. It was here that he met his future wife, Hannah Milner, whom he later married in York. For a while he continued teaching but eventually set up in business as a maker of scientific instruments. A plaque on the Observatory in York Museum Gardens records how Thomas Cooke designed the 1850 refracting telescope housed within that building.

Another former pupil of Pocklington School who was born in Skirpenbeck was Alick Walker, an eminent paleantologist. Born in 1925, he died in 1999.

Nor should we forget James Lloyd of Skirpenbeck, the first self-taught artist to have a work of art exhibited during his own lifetime at the Tate Gallery. He and his family moved to Skirpenbeck in 1950 where he worked first as a cowman and then at Derwent Plastics in Stamford Bridge before finally devoting himself full-time to his painting. A master of the technique of pointillism, he was the subject of a BBC documentary entitled 'The Dotty World of James Lloyd’. James Lloyd died in 1974.

All photographs ©Ruth Beckett. All text ©Ruth Beckett. 2021